Video: Jacques Lacan and the Imaginary-Symbolic-Real

In this [essay] I want to introduce you to psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s concept of the triadic structure of the mind under the notions of the imaginary-symbolic-real formula. However, I not only want to introduce you to this concept, I also want to attempt to convince you that the geometrical structure of the human mind or self-consciousness is fundamentally triadic in its spontaneous movement. Thus, the benefits of this theoretical introduction is to hopefully think in a new way about the problem of consciousness. In contemporary discussions about consciousness we are always thinking about it in terms of neuroscientific reductions to neuronal mechanisms. However, this totally misses the fact that human consciousness cannot be captured objectively from the outside. Consciousness is “in-and-for-itself” and is irreducibly a movement that constitutes our phenomenological and historical reality. In this sense I think that when we think about the problem of consciousness we have to think about it within its natural historical motion; something which Jacques Lacan spent his career trying to understand.

The following images were assembled by a cybernetic theorist Anthony Judge (1). Here you see several famous triadic structures from many different intellectual traditions. What Judge is attempting to show here is that the human mind spontaneously generates and structures its world in triads. Indeed the triad appears as a fundamental structure in many pre-Christian pagan traditions (like the Celtic traditions), in Abrahamic traditions (most notably for example, the structure of the Father-Son-Holy Ghost); however, it also appears in many modern symbols like Francisco Varela’s phenomenological triad of suspension, redirection, and letting go; and also Niklas Luhmann’s communication triad (not shown here) but represented as information-utterance-understanding (2). Thus not only have spiritual and religious systems used the triad, but also some of the greatest phenomenologists and systems theorist of our age have utilized the triad in order to understand the nature of human phenomenology and the nature of human communication.

Here I now want to bring quick attention to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (3). Lacan uses the Phenomenology of Spirit extensively to work through his theory of the unconscious and its relation to history. It is not surprising that Lacan finds the Phenomenology of Spirit as structurally very useful in relation to self-consciousness, desire, and the Other. This is because, as many famous Hegelian scholars have noted, the structure of the book is fundamentally triadic. However, surprisingly, it is not triadic in the sense of the common notion of the thesis-anti-thesis-synthesis (which is misattributed to Hegel, who does not use this triad). Instead it is triadically structured on a meta-level (4). As Howard Kainz notes if one reads the Phenomenology of Spirit one will find quote “thousands of triads” throughout its logical structure. Here one of the most infamous triadic tools that Hegel deploys is the triad of abstract-negative-concrete; which can be understood first as an ideational notion (an abstraction); second as its enaction in a negation of given being (or negative); and third as a concrete transformation or a new interpretation of being (or concrete). In this structural triad we get one of the most important ways in which Hegel thinks about the human mind as a motion of consciousness that negates and re-interprets given being starting in the imaginary realm of abstractions.

Of course, many people have thought of the human mind as a triad. Here I will just highlight a recent philosophical works that also forwards a system of thought that is fundamentally triadic. In Francesco Belfiore book “The Triadic Structure of Mind” we have the notion that mind or spirit is itself a triad organized between intellect, sensitivity and power (5). In this sense we may make a connection between this triadic notion and Hegel’s triadic notion by comparing the intellect to abstraction; sensitivity to negation, and power to concrete. Of course, there may be subtle differences between the way Hegel and Belfiore deploy the triad; but the point is to demonstrate the utility in looking for meta-level patterns between the ways in which different thinkers use triadic structure to understand the motion of consciousness.

Now on to Lacan. Lacan as a psychoanalyst is first and foremost interested in the Freudian revolution which identifies the phenomenon of the unconscious. For Lacan he saw this revolution as reason enough to become an anti-philosopher capable of re-interpreting the history of philosophy under a new gaze due to the discovery of the unconscious. In this Lacan looks closely throughout his career at the work of Plato, Descartes, Kant, Hegel, and Heidegger and seeks to shed new light on the nature of knowledge and thought post-Freud. For example, Lacan will frequently play with Descartes cogito ergo sum (“I think therefore I am”) with unconscious revisions, such as “I think where I am not” — which means that my thought is constantly moving in places and manifesting structures independent of “my self” (i.e. that there is an unconscious knowledge within me). However, in order to structure his thought, Lacan pays the most attention to Hegel, and specifically Hegel’s theory of self-consciousness and the dialectics of desire for recognition throughout history; situating this desire for recognition, not on the level of Master-Slave human conflict but on the level of Master-Slave inhuman love (6):

“The desire of the Other doesn’t acknowledge me as Hegel believes it does. […] It will never acknowledge me sufficiently, […] I can do nothing to break this hold, except to engage with it […] its function doesn’t lie on the plane of conflict, but […] on the plane of love.”

In this way we can see that Lacan is fundamentally interested in a theory of the human mind that can include the unconscious (revising Hegelian dialectics); and also a theory of the human mind that can approach the reconciliation or the impossibility of reconciliation between self-consciousness and its demands for Love in the Other. Here Lacan situates these demands for Love in the Other as connected to his notion of objet petit a; and towards the end of his career; directly related to the site of the Real.

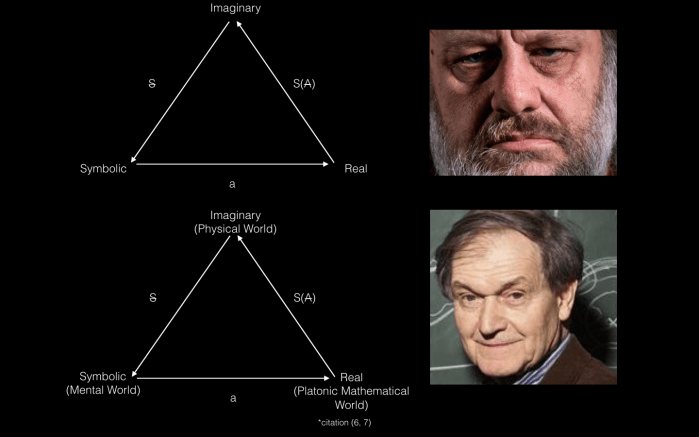

This is one of the final formulations of the Lacanian triadic structure of the human mind that can be found in his late lectures related to the limits of love and knowledge (7). Here you will find Lacan’s notion of the human mind’s most fundamental nature embedded within history in all of its complexity.

We should read this structure in terms of its most elementary coordinates, the coordinates of the imaginary-symbolic-real, and back again to the imaginary. Here we can just intuitively think about what this means. First, we start with our minds in themselves: like think about a normal regular day of being a human mind. In a normal regular day of being a human mind we sleep and find ourself immersed in a dream world, and we awake and find that we can freely think and day dream throughout the day. This is what Lacan places on the level of the imaginary and it is where we start our conscious motion.

Connected to the imaginary, is the level of the symbolic. The symbolic is a transformation of the imaginary into coherent strings of formal information that can be used to more clearly structure our imaginary visions and also to communicate our imaginary visions to others in the structure of speech, writing, and other forms of communication. In this sense, Lacan posits that when we move from the imaginary to the symbolic we are in the domain where subjectivity is moving from the in-itself of its mind to a relationship with the Other (which, you will notice, he marks as “barred” and related to truth). What this means is that the Other, for Lacan, who we are translating our images into symbolism, is fundamentally limited in relation; which means that we cannot merge with the Other. This denotes our irreducible finitude, mortality, and individuality.

(For all the complex Lacanian symbolism I will leave a link to the site “No Subject” in the [Works Cited] which is a fantastic place to learn about Lacanian algebra and core concepts).

Moving on from from the symbolic we now move in the direction of the real, which for Lacan is related to the site of the “missing or barred Other”, and also the site of paradoxical site of enjoyment (here marked by the symbol “J” for jouissance, or sexual enjoyment). Also, in the passage from the symbolic to the real you will notice that Lacan places the “objet petit a” or the object cause of desire on the level of a semblance. What this denotes is that in the translation from the symbolic to the real we are motivated to action by a partial object that causes our motion and directs our attention; in the form of an image of something that we would want to integrate or commune or join with. The idea that this is a partial object is connected to the fact that, for Lacan, when we desire something, we tend to ignore or forget about the rest of Being; instead our attention becomes hyper-focused on one small object out of all the objects in the universe (which is remarkable to think about in that way).

Next we move from the Real and back to the imaginary. Here we encounter, for Lacan, “reality” denoted by the upper-case phi, which in Lacanian algebra denotes the symbolic phallus or the master signifier. Here what this means is that in the motion from the real to the imaginary we form a concrete symbol in our minds about our motion from the imaginary to the real; we detect a gap or a hole in the real and a symbolic appears in this gap or hole which gives us a sense of coherent and consistent internal unity that helps us to structure our future engagements with the real. What Lacan is claiming is that the master signifier or the main signifier that forms in our minds is what our self-consciousness assumes to be “reality” (which you can connect simply with a coherent and consistent notion of your self).

What we learn from this first rotary motion around the structure of the human mind is the idea that in order to understand human consciousness, and its phenomenological embeddedness in historicity, we cannot just understand it by trying to identify neurological correlates in the brain. Whether or not consciousness is “in our brain” somehow produced by the collective interaction of billions and trillions of neurons, misses the phenomenology itself and our daily lives and our daily activities. We miss the flow and the real of consciousness. Thus, when thinking about consciousness we may be able to utilize structures like the one utilized by Lacan in the imaginary-symbolic-real to better understand ourselves and to better understand our motion in day to day existence. Paying closer attention to this structure may allow us to better understand the deepest mysteries of not only our consciousness but the universe itself.

I mean this in a very serious way. For example, consider that the famous mathematician and theorist of general relativity Roger Penrose utilizes a triadic structure in his works The Road to Reality. In The Road to Reality the entire structure of the book is influenced by the idea that there is a fundamental relation between three core elements: what he refers to as the physical world, the mental world, and the mathematical world. For Penrose, he believes that the mathematical world has the most fundamental existence and even exists independently of human beings and the physical world, in what he refers to as a Platonic superspace or a Platonic transcendental space. This is actually a very common belief in the mathematics and physics community, it is indeed also the structure of the works of Max Tegmark’s book Our Mathematical Universe.

However, what I have done here is taken the liberty of structuring Penrose’s works under the triadic coordinates of the Lacanian psychoanalysis. Thus, instead of assuming that there is actually a Platonic transcendental superspace; we instead situate what Penrose calls a Platonic transcendental superspace on the level of what Lacan calls the Real. In that sense we see that Penrose is not interacting with a totalizing sphere independent of all human minds and all physical reality; but instead is interacting with the object cause of his desire; which is a totalizing understanding of the whole of mathematics. Here we can say that Penrose’s real emerges from his imaginary-symbolic transformations with the world; which primarily take place in relation to the social systems of physics and mathematics. Thus it is not surprising that his most fundamental desire take the form of a transcendental mathematical world.

Here I would posit that this is more than just a psychoanalytic observation, but a fundamental observation, because we can rethink the “road to reality”. The road to reality is not out there in the external world, either physical or transcendental; but right in here, in how our human consciousness interacts with the real in a triadic motion.

(You can help my efforts by becoming a supporter on Patreon).

Works Cited:

(1) Judge, A. 2017. Framing Global Transformation through the Polyhedral Merkabah. laetus in praesens. https://www.laetusinpraesens.org/docs… (accessed: Feb 20 2018).

(2) Lenartowicz, M. 2017. Creatures of the Semiosphere: a problematic third party in the humans plus technology cognitive architecture of the future global superintelligence. http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/ECCO/ECCO-papers/Lenartowicz-CreaturesSemiosphere.pdf (accessed: Feb 21 2018).

(3) Hegel, G.W.F. 1998. Phenomenology of Spirit. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

(4) Kaufmann, W. 1966. Hegel: A Reinterpretation. New York City: Anchor Books. p. 37.

(5) Belfiore, F. 2014. The Triadic Structure of the Mind: Outlines of a Philosophical System, 2nd Edition.

(6) Lacan, J. 2014. Punctuations on Desire. In: The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book X: Anxiety 1962-1963. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller, Translated by A.R. Price. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 153.

(7) Lacan, J. 1999. Chapter VIII. Knowledge and Truth. In: On Feminine Sexuality, The Limits of Love and Knowledge, 1972-1973. Book XX. The Seminar of Jacques Lacan. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. New York: W.W. Norton.

(8) Žižek, S. 2014. From Here to Den. In: Absolute Recoil: Towards a New Foundation for Dialectical Materialism. London: Verso.

(9) Penrose, R. 2004. The roots of science. In: The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. London: Jonathan Cape.

Other resources: